Creating a monster for any OSR system is the easiest thing in the world, you don’t even need a detailed guide or deep rules, just fill out this form:

AC: ___

HD: ___

hp: ___

MV: ___

#ATT: ___

DMG: ___

ML: ___

SPECIAL: ___

When creating a monster, don’t stick to the rules of character creation, monsters can, and indeed should, break the rules.

Let’s have a closer look.

Armor Class (AC)

Assume that the AC is 12 when a character wears no armor, 14 when wearing leather armor, 16 when wearing chain mail, and 18 when wearing full armor. Some games use descending AC, where the better the armor, the lower the number. See this table of equivalences.

Monsters usually don’t wear armor, unless you consider orcs and goblins to be monsters, in which case the real monster is you. So what we must do is think about how easy or difficult it is to hit a monster, and we can use these values to guide us, but we must not follow them to the letter, that is to say that you can give an AC of less than 12 or more than 18 if you consider it should be so, just keep in mind that a 10 or less might be trivial, and a 20 or more, might be impossible.

Hit Dice (HD)

In addition to armor, HD helps us define how durable a monster is: the higher its HD value, the more hit points it will have, so you need more successful attacks to kill it.

HD also determines how powerful a monster is and how easy it is for it to make its attacks. Although each system calculates the attack bonuses of monsters according to their HD differently, all these systems are similar. Let’s say that each HD translates into a bonus equal to its value; thus, a monster with 5 HD gets a +5 to its attack roll.

Hit Points (hp)

The standard method is to roll a number of d8 equal to HD, so 5 HD translates into 5d8, and the result of that roll is the monster’s hp, but we’re not gonna be making that roll every time a monster appears, so we’d better use the average value.

This value is obtained by multiplying the number of HD 4 or 5 times. Thus, our 5 HD monster would have on average between 20 and 25 hp.

Depending on the role of the monster in the adventure where you want to use it, you can reduce or increase this number.

An ordinary monster might have 1 or 2 hp per HD, but if the monster is the main enemy, consider giving it 6, 7 or even 8 points per HD (in our example, between 30 and 40 hp).

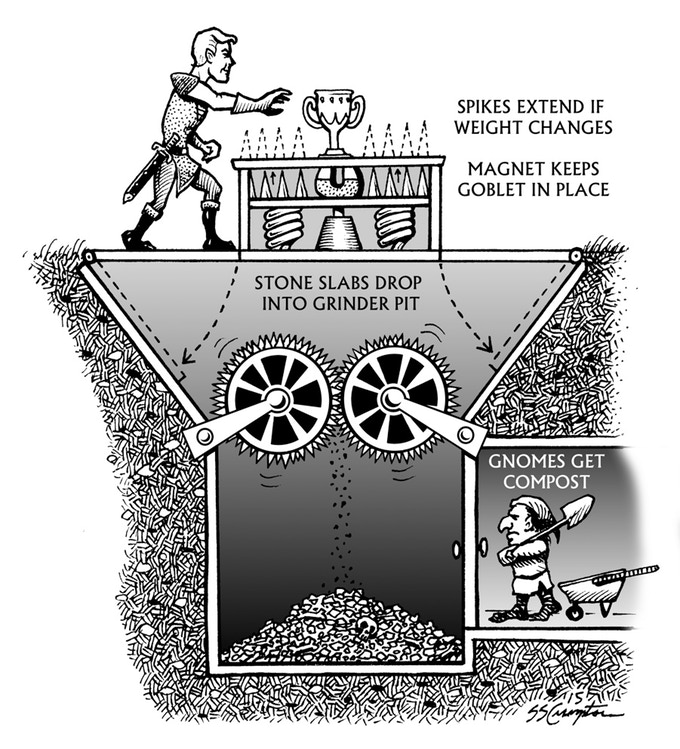

Keep in mind that the stronger and tougher it is, the more likely it is to cause a TPK. Consider alternate ways to cause it damage if the players are smart, such as luring it into traps, shooting it from a safe area, or something similar.

Movement (MV)

As a base, use standard human movement, which is 120 feet per exploration turn (10 minutes), 40 feet per combat round, and 120 feet per combat round when running but taking no other action.

How fast or slow is your monster? Equal to a human, half the speed of a human, twice the speed of a human?

To keep it simple: Standard, half, double, or more than human; in feet this translates to:

- 120′ (40′)

- 60′ (20′)

- 240′ (80′)

- 180′ (60′)

Accuracy is irrelevant, the important thing is to know if the monster is going to catch us if we try to run away or how long it would take us to catch it if we want to recover the gold ring that our partner who has been eaten by the monster was wearing on his finger.

These values correspond to the speed of the monster on the ground, some creatures may have another mode of movement with a different speed, for example flight. We write it down like this:

- MOV: 120′ (40′), flight 240′ (80′)

That is, on the ground it moves with the same speed as a person, but when flying it’s twice as fast.

Number of Attacks (#ATT)

You don’t need to complicate things, as a general rule all monsters can perform only one attack per round.

But some monsters must break the rules, right? A radioactive octopus can maybe hit with 8 of its tentacles each round, in which case you’ll write down this:

If it can squirt radioactive ink, but can only do one of the two types of attack per round, you write it down like this:

On the other hand, if it can attack with tentacles and ink in the same round, you write it down like this:

If you want it to have other attacks, follow the same principle, but write down all the ones it can do during the same round one after the other, and then the ones it cannot. Following the example, if our octopus can launch a mental discharge, but to do so he must concentrate and not do any other action, it should be written down like this:

Damage (DMG)

To decide how much damage each attack does, compare the attacks with common weapons. Depending on the type of weapon, the damage may be 1d4, 1d6, 1d8 or 1d10 (although some systems may include other values).

- d4: Knive, club, cane

- d6: Short sword, hand axe

- d8: Standard sword, battle axe, mace

- d10: Two-handed sword, great axe, maul

Let’s say each tentacle hits like a whip, how much damage does a whip do? 1d3 damage.

The ink does no harm, but it can blind an enemy.

Mental discharge can cause 1d8 damage due to the strong emotional charge it represents.

Assuming that our octopus can strike with the tentacles and throw the ink in the same round, but the mental discharge can only be done separately, we would write it like this:

- #ATT: 8 and 1, or 1

- DMG: 8 tentacles 1d3 and Special, or 1 psycho blast 1d8

Note that we write down each type of attack followed by the damage; this can be used to eliminate the line for the number of attacks per round, but it is advisable to leave it for clarity.

In a moment we will explain “special”.

Morale (ML)

The morale value is a number between 2 and 12. When you need to know if an enemy surrenders or tries to flee, or if it continues to fight during an encounter (usually when it has suffered more or less considerable damage or its party has suffered many casualties), you make a morale check, rolling 2d6. If the result is equal to or less than the monster’s ML, it keeps fighting; if the result is higher, the creature tries to flee (or surrenders, if your monster is an orc or goblin).

It’s impossible to get more than 12, so a ML of 12 means that the creature may fail this roll, is unaware and will fight to the death, or has lost all interest in its own well-being.

To understand it clearly, morale means “will to fight”. Passing the morale test means that the will to fight is still intact, failing means that it has lost its will.

Special

All information that cannot be abstracted with a simple numerical value or that requires further explanation is placed here.

In the case of our octopus, the ink jet does not cause quantifiable damage (a numerical value) but has the possibility of blinding the target. Can this attack be dodged, does the octopus roll its attack die, or how does it work mechanically?

This is one possibility:

- Special: The octopus squirts a blast of ink at a target; the player must make a saving throw vs. breath weapons to prevent the ink from touching her eyes. If she fails, she can’t act for 1d3 rounds until the ink effect ends, or a single round if she can wash her face and eyes immediately.

This is another:

- Special: The octopus squirts a blast of ink making a normal attack roll against a target, if successful, the target can’t act 1d3 rounds until the ink effect ends, or a single round if she can wash her face and eyes immediately.

Both methods are equally valid, in some cases one may be easier or more difficult to avoid, but don’t worry about that, choose the one you consider more natural, you can even have two identical monsters with the only difference that one uses the first method and the other uses the second.

Now it’s time to show off our finished creation.

Psychopus

An octopus the size of a horse. Its color varies according to its mood (make a reaction roll; the more hostile, the more purple; the friendlier, the whiter).

AC: 11

HD: 5

hp: 20

MV: 60′ (20′), water 240′ (80′)

#ATT: 8 or 1 or 1

DMG: 8 tentacles 1d3 or Special or 1 psycho blast 1d8

ML: 9

SPECIAL: The octopus squirts a blast of ink at a target; the player must make a saving throw vs. breath weapons to prevent the ink from touching her eyes. If she fails, she can’t act for 1d3 rounds until the ink effect ends, or a single round if she can wash her face and eyes immediately.

Note how I wrote the damage. My monster can only make one type of attack per round, either tentacle lash, or ink, or blast.

Final words

Making monsters for your games should be quick and easy, not a chore. It can feel arbitrary, but once you get the hang of it, you can make a monster in less than a minute and it won’t be totally random. Spend a couple more minutes and you can make a reasonably interesting monsters that fits well in your game. Make a bunch and it will become second nature in no time. Need some inspiration?

OST

While I was writing this, I was listening to this playlist.